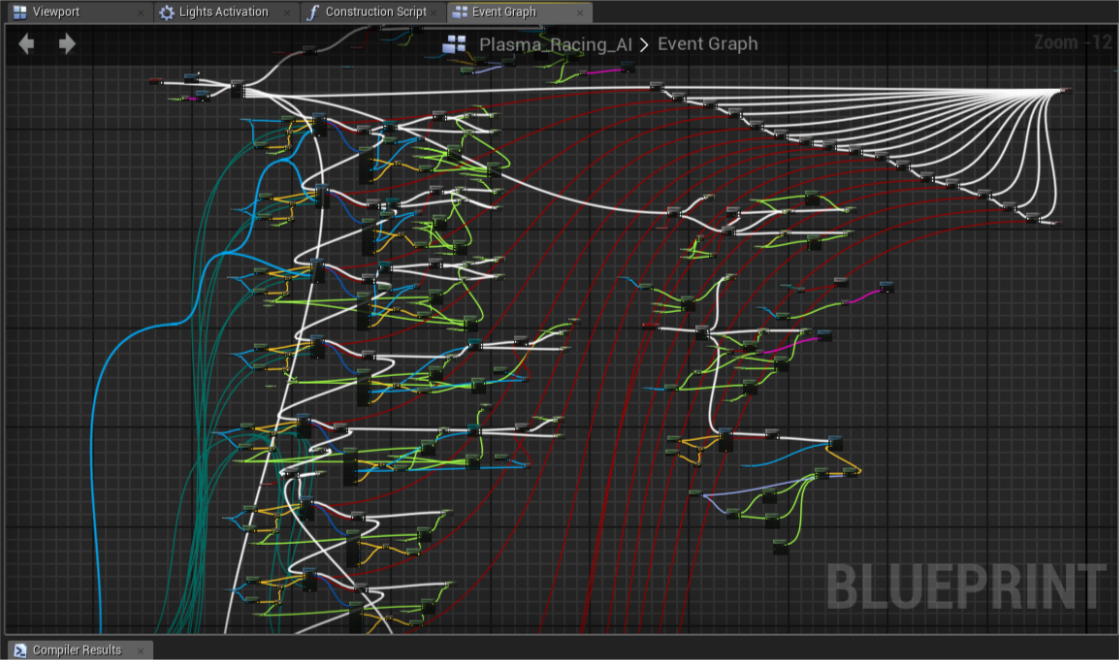

Performance guideline for Blueprints and making sense of Blueprint VM.

Thanks a lot to Bry and WizardCell for contributing to this article.

You can see many people telling these innocent lies all over the place:

- Avoid tick, it’s expensive

- Use timers instead of tick

- Do not use cast, its expensive

- Prefer interfaces instead of casting

- Use timelines instead of tick

and sadly there are many projects following those advices, especially the ones implement 100% Blueprints without any C++ code. So over the time I ended up developing a motivation to research how Blueprints works behind the scenes, and decided to write an article about it. So today we are going to go through those common myths and explain why they are incorrect, and analyze actual problems of Blueprint system. 😎

But before going through myths, let’s examine how Blueprints virtual machine actually works behind the scenes, so we can reason logic behind it.

Understanding the infastracture of Blueprint system.

Blueprints is a visual and interpreted language that is implemented on top of Unreal Engine 3’s UnrealScript virtual machine. As today’s date, it outperforms old UnrealScript VM, but also shares most of the limitations of it, like not being able to expose arrays of arrays to reflection system and lack of support of various types from natively supported property system.

Meet the magic called “bytecode”!

Programming languages has “back-ends” and “front-ends”. Front-end, in this context, refers to user-facing side of the language. You can think of a programming language’s syntax, rules and grammar when I say front-end. Meanwhile, back-end refers to the abstract machine that runs the actual logic that your code is compiled into.

Blueprints, as we mentioned above, is running on a very old abstract machine that we call “virtual machine” that is written around 1998 by Tim Sweeney himself.

Unreal’s script solutions, until Verse is announced, always ran on the same virtual machine, but in different forms. Based on a tweet by Tim Sweeney, first Unreal had a Visual Basic style of syntax, then it evolved into a C-like language with operator overloads and such, and in the end, after Epic decided to kill UnrealScript, it became a visual scripting system.

The instructions Blueprints virtual machine can execute is called bytecode. A bytecode is an operation that a virtual machine can execute. Blueprints VM can call functions, set values to each other, can jump into different paths of code (i.e. the Branch node), can run recursive code (loops) and do many other esoteric stuff that you don’t need to know.

A compiler is responsible of compiling the user facing format into bytecode that virtual machine can run. Blueprints compiler, reads all of your nodes that you placed into graph and converts them into bytecode.

Some other languages, like C++, Rust and Erlang compile into machine code rather than bytecode. This makes them faster to run, because, essentially, a virtual machine is a code that is written in an already existing language that “acts like” CPU. Just like virtual machines, our CPUs also has predefined instructions that they can run. But since they directly run on hardware, it’s way more faster than evaluating bytecode in a different programming language’s boundaries.

So why we are using bytecode then, instead of compiling Blueprints into machine code? Because it’s not that easy! 😄

“Compiled languages”, unlike “interpreted languages” like Blueprints that run inside of virtual machines takes too long to compile and often very difficult to provide a managed environment where accessing a null variable doesn’t crash your whole program immediately.

You also have the benefit of being able to compile your code in milliseconds and run it directly, without bothering other layers of processes compiled languages introduce.

How are Blueprints interpreted?

There is a deep relation between multiple complex frameworks like garbage collector, blueprint graph, UObject, UClass, UBlueprint classes etc.

But to explain things simply:

-

Blueprint graphs acts like containers for blueprint nodes, it’s our “front-end” that is exposed to us when we’re coding in Blueprints.

-

Each blueprint node is represented as

UK2Nodeclass in C++ and everyUK2Nodecan provide information as to how it’s going to be compiled into bytecode. The nodes we use to call functions, the branch node, the cast node, they all have custom code in C++ side to define the behavior of the code you’re writing in blueprints. If you’re programmer, definitely look atUK2Node::ExpandNodefunction if you’re interested in details. -

All nodes generate an “intermediate representation” called

Kismet Compiler Statementthrough theUK2NodeAPI. -

All

Kismet Compiler Statementget compiled into bytecode and saved into the class/function data.

Blueprints is essentially something like a “machine” that calls C++ code.

Majority of the interpreted languages in the software industry will try to act like a CPU as much as it’s possible. But Blueprints VM is rather designed like a “function caller”, instead of a proper VM or an interpreter that mimics CPU instructions.

When you write your code in blueprints graph, if you take it as a whole and analyze it, you will see at least around 95% of it is just making calls to native functions or the blueprint functions you wrote. You will see other languages, like javascript has quirky “deoptimization” penalties when you write your code in different forms, even though sometimes they evaluate to same result. This is because their front-end, as a text-based language is more expressive than a graph that you put nodes and connect them to each other. Because their compiler transforms the code with deeper representations internally.

But this is not the case in Blueprints, since we’re mostly limited with a few nodes that has the ability to control the execution flow of our code and rest of the nodes are simply all about calling functions.

While this is a bit limiting, this is also what makes Blueprints VM is very comprehensive. If we would want to integrate another language into Blueprints system, this would be pretty easy (relative to other dark stuff involved in this type of processes). Right now, at the date this article is written, Verse is also being compiled to Blueprints VM to run in UEFN!

So, what I’m trying to say is, BPVM only has one meaningful overhead, and it’s “calling functions“!..

We’ll see more in detail below.

Some fun facts before we dive into deeper topics

-

First name of the node based visual scripting system was “Kismet” and it’s still referenced as it is in the source code instead of “Blueprints” most of the time.

-

Some base ideas of Verse still inherits concepts from how Blueprints virtual machine’s design, like “persistent memory” system and latent nature of the language.

-

When you execute a node in event graph, until the object is destroyed, all of the return pins preserve their original values. This concept is called “ubergraph frame” and required for latent nodes to work internally in the event graph. So, nothing in the event graph is local memory. Every pin is declared in the heap memory and their lifetime is bound to the owning object.

-

The “ubergraph frame” is a pseudo-struct (generated in runtime when object is spawned based on reflection data) that contains all nodes return and output parameters inside of it. And it is technically part of the class memory - so as your event graph(s) grow, the total size of the object/class in the memory also grows.

Performance of Blueprints (Direct overheads vs indirect overheads)

The Blueprint System has “direct” and “indirect” overheads.

Direct overheads refer to overhead that is generated by base execution implementations of the virtual machine, while indirect overheads are caused by Blueprints’ compilation model.

There is only one direct overhead Function calls (node evaluation).

Everytime the Blueprint VM evaluates a function, it just runs a code to invoke the C++ function. And even if you have a function/event you created in Blueprint graph, you just end up calling functions declared in C++ inside of it. When you start up a fresh project in launcher, every existing function you can add to blueprint graph is defined in C++. The Events that are automatically added to graph when you create a new Blueprint class, like BeginPlay, Tick, OnBeginOverlap are also actually C++ functions called by engine.

Every function “call” ALMOST has the same exact overhead. Behind the scenes, Blueprints VM runs same code to evaluate every node in the graph.

In the video, Epic claims calling functions almost has the same overhead in Blueprints, but it’s actually incorrect. The more parameters and the more complex/bigger types you have, the more it will be expensive to call a function. Don’t let this info misguide you and try to optimize your way into reducing parameter counts in your functions though, that’d make very minimal effect on performance. Always focus on profiler results!

If you are familiar with Python, you probably already know most of the common packages are actually written in different languages to provide faster execution speed. You might even see many people advise avoiding implementing data structure algorithms and using what packages provide. (i.e. like using max() or min() functions instead of looping through gigantic lists).

We can apply the same philosophy to Blueprints too. There are many operations that you can implement in C++ to outperform Blueprint performance by 20x in regular gameplay code. The less nodes you have in a graph, the less instructions VM will have to execute. So if you are after optimizing your blueprint code, the only thing you can do is reduce the amount of nodes to execute.

If you take a look at Kismet Libraries that is implemented in Unreal Engine’s source code (the static helper functions for math, line traces, overlap checks etc) that’s actually what Epic Games is trying to do. Wrapping expensive to run operations in C++ and letting user get away with single function call overhead in the Blueprints graph. Imagine having to loop through all possible overlaps and querying them in blueprints instead of using Sphere Overlap by Actors… It would be a terrible experience for your poor CPU! 😛

So, alongside with moving things into C++ during development as you need more performance, if you’re not a programmer already, learning a few bits of C++ to at least offload some stuff from Blueprints to C++ side would be very helpful for you.

Indirect overheads.

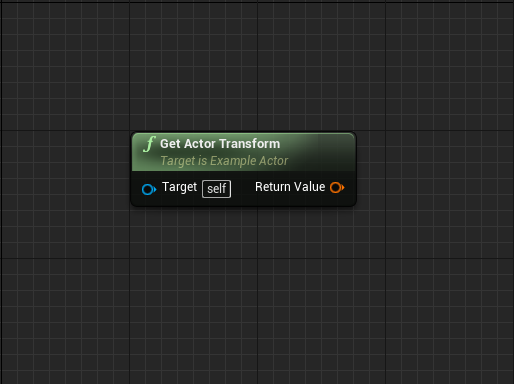

Pure nodes can be dangerous, because they are evaluated each time they’re plugged to an input parameter.

There are two types of Blueprint functions:

- Impure nodes

- Pure nodes

Impure Nodes

- Impure nodes are blue nodes that have Execution pins.

- When impure nodes are evaluated, their outputs become local variables within the blueprint graph. So each time you call an impure function, Blueprint VM will create (hidden) local variables for each output parameter. So if any of the output params are connected to one of the next function’s input parameters, BP VM will access the hidden local variable it created when that node was executed last and use it.

- If you have multiple output params that are expensive to copy (like multiple non-primitive types like vectors, rotator and custom structs), you should prefer using an impure function.

Pure nodes

- Pure nodes are green nodes that do not have any Execution pins.

- When a pure node is evaluated, they are being invoked for each line that comes out of their output.

- You should never have expensive to run functions as pure nodes because of that.

- They work best for providing references of objects and simple (blocks of) math operations.

- “Get” nodes of variables are also pure functions.

- Use pure nodes with caution when you are in a loop body. Prefer to cache variables before running a loop and accessing the cached variables instead.

Parameter prepration and copy cost.

Each time you call a function, you trigger a chain of virtual calls that copy and initialize the parameters of the function inside of the VM.

The dependency to virtual functions is one of the reasons what makes Blueprint VM is extremely slow.

- Each time you call a function, there is a cost of setting variables per input and output params, even if nothing is connected to the pins.

- However, with modern computers this is a cheap operation and almost NEVER a performance concern. Of course this also depends on how many inputs / outputs there are in that Blueprint function.

Setting a variable means “copying it”.

As said, modern computers can handle simple operations like setting a variable, but we should not forget that setting a variable means copying a value to it. For example, if you do:

float myValue = 3.f;

float myNewValue = myValue;

you would copy 4 bytes of value from myValue to myNewValue. And this is perfectly fine. But what if you copy something like this?:

FVector vectorArray[4096];

FVector newVectorArray[4096] = vectorArray

You would copy around 50 kilobytes of data (12 bytes * 4096) which, again, is most likely still going to be fine for a modern CPU unless you repeat this action multiple times at once. Blueprints does this all over the place and hides this operation from the front-end user interface.

Also, since Blueprint functions input params by default are set to be passed by copy, you should not copy arrays or should not have too many output params. You can prevent copying passed-in arguments by marking the arguments of a Blueprint as “Pass-By-Reference”.

The image below shows a function that takes in 2 arguments. One is passed by reference and the other one is passed by value. The reference will not have the extra instruction of creating a new temporary variable whereas the pass by value will.

Also notice how pass-by-ref argument pins do not allow you to set a “default value” because they expect you to pass a reference to a variable that already exists. The pass by value however gives you the option to provide a default value.

When calling the function, you can see the pass by reference pin is now a diamond which signifies that this variable needs to be passed by reference. Which also means that you can’t “set” it’s value to anything, you have to pass it a variable that exists!

With that being said, if the passed-by-ref variable is changed within the function, that variable will be whatever it’s value was changed to outside of that function.

Back to the Pure Function discussion, here’s an example from a while ago. Someone posted this image in reddit and people wondered what would happen if you actually ran this function:

Before seeing the overhead of the function, you would see the overhead of your CPU trying to copy values for input params and overhead of instantiating them as (hidden) variables. It would be a terrible experience for your CPU 😄

There is a reason the Blueprint system is considered a scripting language. If possible, you should definitely avoid writing system architecture with it.

Make and Break nodes of structs

For each struct you have in your project, Unreal Engine generates a default Make and Break nodes. These nodes aren’t different from any other functions in terms of input/output param handling. So each time you use a Break Hit Result node you end up copying almost every variable in the hit result, even though some of the pins are unused.

Converting Blueprints to C++ auto-magically

During the time I was writing this article I was developing my own Blueprint to C++ transpiler called BP2CPP. And unsurprisingly everything I wrote here was a byproduct of my ongoing research to how to accomplish something that is so complex and difficult even Epic Games gave up on their attempts with UE5.0.

So, allow me to advertise a bit 😇

BP2CPP is “nativization made possible” - a plugin I created that works differently from the official one that got removed.

BP2CPP offers up to ~15x faster execution speed compared to Blueprints VM, with the ability of converting all of your Blueprints to C++ with a single click and optionally through automation support so you don’t have to click buttons everytime you ship your project.

BP2CPP has no limitations regarding to usage of Blueprints, which means everything you can place to your graph is supported, including third party plugins and custom tooling as long as it gets compiled to Blueprints system.

BP2CPP is not a dumb code generator, it’s a complete badass transpiler with multiple optimization passes that makes the generated code runs extremely efficiently without ever modifying the original content or data of the Blueprints assets.

Myths

Now finally let’s talk about myths of the Blueprints language!

Myth 1: Avoid tick, it’s expensive.

As explained above, the only direct overhead of Blueprints system is the function invoking overhead. A simple tick event won’t destroy your performance on it’s own, but the nodes connected to your tick event will run every frame and memory access to instructions can end up being way slower than C++ code. Unless you are going to ship to low-end hardware like a PS4, you do not need to avoid tick in every situation. Always profile your game in shipping config at the lowest hardware target you plan to release on.

I wanted to provide data about overhead of executing a single empty tick node on lower hardware, but I don’t have access to any low-end hardware to profile against. However, for what it’s worth, I have heard calling around 300 empty tick nodes in a single frame costs around 1ms per frame. One way or another, try to never believe anything anyone says - except everything I just said in this post - unless you profile it yourself to see the performance with your own eyes.

Myth 2: Use timers instead of tick.

Also don’t forget the red square pin you are plugging an event to Set Timer by Event is a dynamic delegate (event dispatcher, in BP terms) and it’s expensive to call. 100 BP ticks vs 100 Dynamic Delegate invoking will end up in a result dynamic delegates causing more of overhead than BP ticks.

Though that doesn’t mean you shoud always prefer tick for everything. There are times timers can be useful against tick, but you should not try to replace tick function with timers for performance reasons.

Myth 3: Do not use cast, its expensive

“Cast” itself is nothing but a fancy loop that goes through class hierachy data in reflection system. If the given class type is found in the loop, the engine does a C-style cast to given type (which is… literally free for CPU to execute) and returns a pointer to it.

The reason people say “cast is expensive” is, when you reference something in your blueprint class, the engine automatically loads those references along with your Blueprint into memory. You should prefer using soft references and design your systems properly to avoid loading half of the game with a single blueprint class. I’ve seen “blueprint function libraries” that have reference(s) to boss characters of the game in the input parameters of their functions, and end up loading at least 2GB of data into memory for absolutely no reason. 🤦♂️

So try not to have hard references to memory intensive blueprints in your graph instead of avoiding cast.

Myth 4: Prefer interfaces instead of casting

Interfaces are some sort of “multiple inheritance” thing and their existence is not meant to replace casts.

An interface is a description of the actions that an object can do. For example when you flip a light switch, the light goes on, you don’t care how, just that it does. One actor might implement it this way, another actor might implement in that way. This is where interfaces are useful.

In fact, behind the scenes the engine actually does a cast to access the interface in given object. So people who are using interfaces because of this “Do not use cast” myth are actually not ending up avoiding any cast.

Myth 5: Use timelines instead of tick

Each timeline node ends up being a component in your actor class and costs memory. They are great for evaluating curves and they also provide some cool inline curve editor that you can open and edit your curves inside of the actor’s blueprint graph, but it has disadvantages too:

- Each timeline node also ends up being another “tick function register” for engine’s “tick manager”.

- Tick manager queues, updates and checks the state of the registered tick functions. So having too many timelines can result in a slight bottleneck for the tick manager.

- Having too many timelines cause actor to instantiate and register a component which is surprisingly more expensive than just instantiating. So it ends up making the actor more expensive to spawn.

I’d say, use timelines, but do not replace tick with them. They are good for sequential ticks that are enabled and disabled at specific times and also when you require the evaluation of a curve too.

That was all. Thanks for reading! Make sure you share this article with any friends that you may have that are still wearing a tin hat! 😊